September 16, 1903

written by Steve Murray

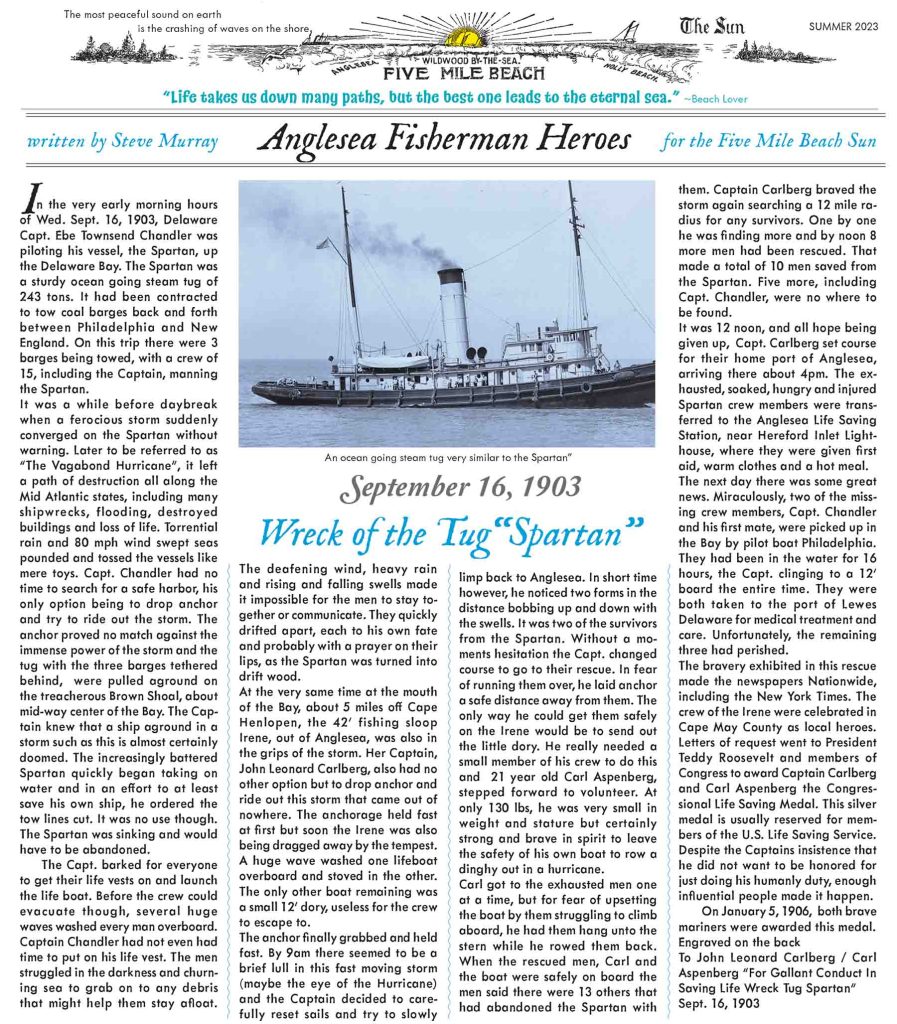

In the very early morning hours of Wed. Sept. 16, 1903, Delaware Capt. Ebe Townsend Chandler was piloting his vessel, the Spartan, up the Delaware Bay. The Spartan was a sturdy ocean going steam tug of 243 tons. It had been contracted to tow coal barges back and forth between Philadelphia and New England. On this trip there were 3 barges being towed, with a crew of 15, including the Captain, manning the Spartan.

It was a while before daybreak when a ferocious storm suddenly converged on the Spartan without warning. Later to be referred to as “The Vagabond Hurricane”, it left a path of destruction all along the Mid Atlantic states, including many shipwrecks, flooding, destroyed buildings and loss of life. Torrential rain and 80 mph wind swept seas pounded and tossed the vessels like mere toys. Capt. Chandler had no time to search for a safe harbor, his only option being to drop anchor and try to ride out the storm. The anchor proved no match against the immense power of the storm and the tug with the three barges tethered behind, were pulled aground on the treacherous Brown Shoal, about mid-way center of the Bay. The Captain knew that a ship aground in a storm such as this is almost certainly doomed. The increasingly battered Spartan quickly began taking on water and in an effort to at least save his own ship, he ordered the tow lines cut. It was no use though. The Spartan was sinking and would have to be abandoned.

The Capt. barked for everyone to get their life vests on and launch the life boat. Before the crew could evacuate though, several huge waves washed every man overboard. Captain Chandler had not even had time to put on his life vest. The men struggled in the darkness and churning sea to grab on to any debris that might help them stay afloat. The deafening wind, heavy rain and rising and falling swells made it impossible for the men to stay together or communicate. They quickly drifted apart, each to his own fate and probably with a prayer on their lips, as the Spartan was turned into drift wood.

At the very same time at the mouth of the Bay, about 5 miles off Cape Henlopen, the 42’ fishing sloop Irene, out of Anglesea, was also in the grips of the storm. Her Captain, John Leonard Carlberg, also had no other option but to drop anchor and ride out this storm that came out of nowhere. The anchorage held fast at first but soon the Irene was also being dragged away by the tempest. A huge wave washed one lifeboat overboard and stoved in the other. The only other boat remaining was a small 12’ dory, useless for the crew to escape to.

The anchor finally grabbed and held fast. By 9am there seemed to be a brief lull in this fast moving storm (maybe the eye of the Hurricane) and the Captain decided to carefully reset sails and try to slowly limp back to Anglesea. In short time however, he noticed two forms in the distance bobbing up and down with the swells. It was two of the survivors from the Spartan. Without a moments hesitation the Capt. changed course to go to their rescue. In fear of running them over, he laid anchor a safe distance away from them. The only way he could get them safely on the Irene would be to send out the little dory. He really needed a small member of his crew to do this and 21 year old Carl Aspenberg, stepped forward to volunteer. At only 130 lbs, he was very small in weight and stature but certainly strong and brave in spirit to leave the safety of his own boat to row a dinghy out in a hurricane.

Carl got to the exhausted men one at a time, but for fear of upsetting the boat by them struggling to climb aboard, he had them hang unto the stern while he rowed them back. When the rescued men, Carl and the boat were safely on board the men said there were 13 others that had abandoned the Spartan with them. Captain Carlberg braved the storm again searching a 12 mile radius for any survivors. One by one he was finding more and by noon 8 more men had been rescued. That made a total of 10 men saved from the Spartan. Five more, including Capt. Chandler, were no where to be found.

It was 12 noon, and all hope being given up, Capt. Carlberg set course for their home port of Anglesea, arriving there about 4pm. The exhausted, soaked, hungry and injured Spartan crew members were transferred to the Anglesea Life Saving Station, near Hereford Inlet Lighthouse, where they were given first aid, warm clothes and a hot meal.

The next day there was some great news. Miraculously, two of the missing crew members, Capt. Chandler and his first mate, were picked up in the Bay by pilot boat Philadelphia. They had been in the water for 16 hours, the Capt. clinging to a 12’ board the entire time. They were both taken to the port of Lewes Delaware for medical treatment and care. Unfortunately, the remaining three had perished.

The bravery exhibited in this rescue made the newspapers Nationwide, including the New York Times. The crew of the Irene were celebrated in Cape May County as local heroes. Letters of request went to President Teddy Roosevelt and members of Congress to award Captain Carlberg and Carl Aspenberg the Congressional Life Saving Medal. This silver medal is usually reserved for members of the U.S. Life Saving Service. Despite the Captains insistence that he did not want to be honored for just doing his humanly duty, enough influential people made it happen.

On January 5, 1906, both brave mariners were awarded this medal.

Engraved on the back

To John Leonard Carlberg / Carl Aspenberg “For Gallant Conduct In Saving Life Wreck Tug Spartan”

Sept. 16, 1903