by Steve Murray

A deed was signed on July 7, 1873 between the owners, Humphfrey S. Cresse and his wife Ruhannah and the United States of America, selling the said parcel and also “allowing free and unrestricted right of and thoroughfare for all purposes pertaining to the erection and maintenance and use of a lighthouse.” The sale price was $150.

The Lighthouse Board ordered a lighthouse “to be built in accordance with class C, 4th Order Harbor Lighthouse and Keeper’s dwelling.” A structure designed by the Board’s Chief draftsman, Paul J. Pelz was chosen for the site.

In October of 1873, a contract was signed between the US Lighthouse Board and Hurst-Marshall Contractors of Philadelphia. They were to build Hereford Inlet Lighthouse for the bid price of $14,740.93. There was to be a $10.00 per day forfeit by the company for each days delay completing the job.

Lieutenant Col. William Reynalds, Brevet Brigadier General, US Army Corps of Engineers, would oversee the entire project.

A skilled crew of craftsmen employed by Hurst-Marshall arrived by boat from the mainland. There were master carpenters and masons, apprentices and journeymen. Some of these men would spend the next six months on the lonely, wind swept island until the Lighthouse was completed. They worked a very long day, probably dawn till dusk, six days per week.

The sight was cleared and graded and a temporary building was constructed first to house the workers, tools and supplies.

Norma Neill Seagraves, formally of North Wildwood, said in an interview several years ago that her great-grandmother, Emma Hankins, was hired as the cook for the workers. She was not certain what the housing arrangements were for her grandmother but it is certain she also stayed at the site until the work was completed.

Much of the lumber, hardware, bricks, millwork and other materials came by train to Cape May Court House. It would then be transported by wagon to the Landing at Mayville and then over by boat to the island. Some of these materials such as cedar shakes for the roof and cedar siding probably were of local origin, coming from the mills of Dennisville.

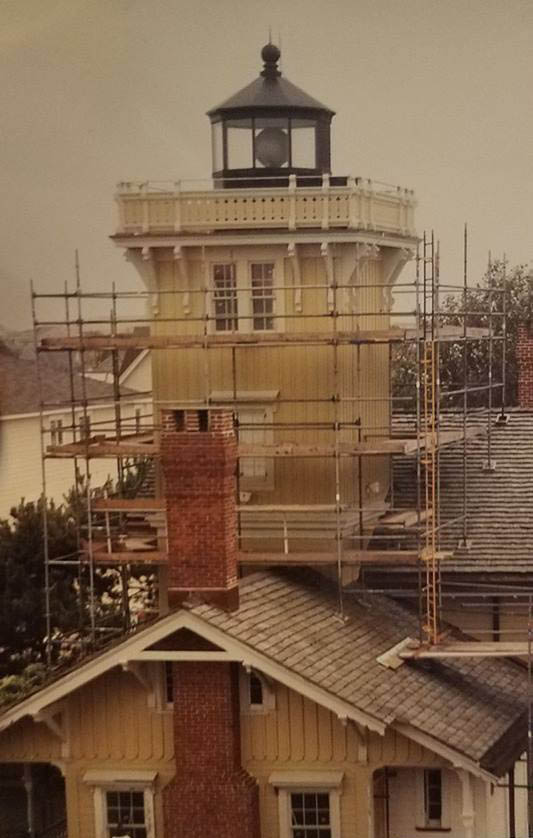

Working through those long winter months on the beachfront must have been miserable much of the time. Some interesting evidence was discovered during renovations in the Summer of 2003. There were many seemingly unnecessary original nails on the westside of the building. We suppose that on some of the worst days the carpenters hated to leave the protection of the leeward side of the house and just kept hammering to keep warm and look busy.

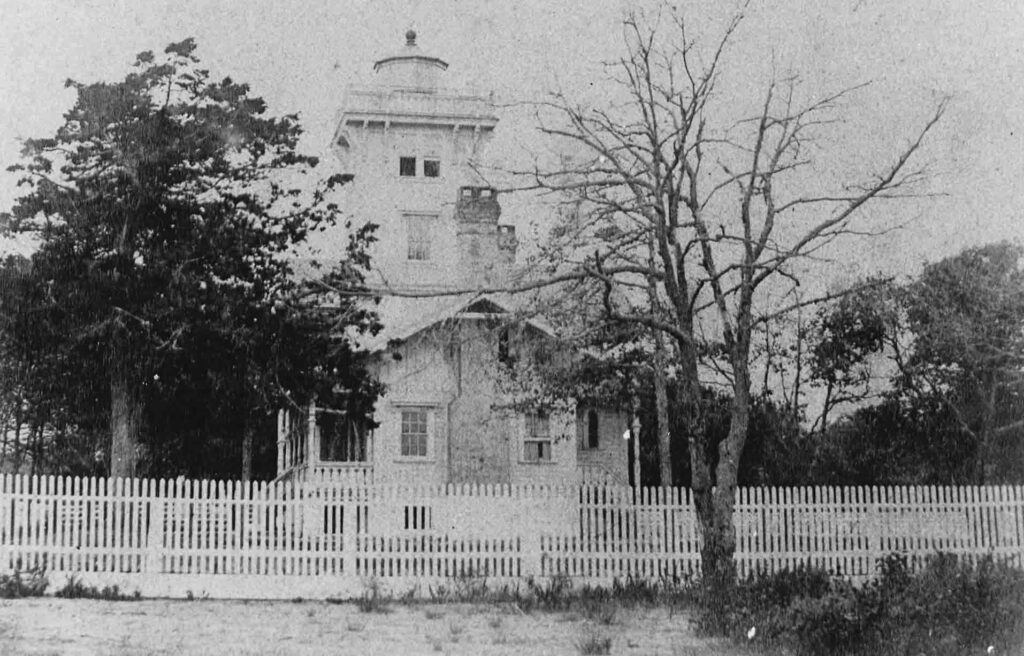

The building that slowly revealed itself was absolutely beautiful. The architectural style of this design by Pelz can be called Victorian Carpenter Gothic (with Swiss Chalet influences.) It can also be referred to as “Stick Style”, because of the exposed “stick work” such as post with brackets that support beams and exposed rafters that support projecting roofs.

The configuration of the building was a “T” plan. One half of the house ran perpendicular to the other half. A tower straddled the roofs of both. The living quarters of the house were located on the first two floors. There was a large kitchen with walk-in pantry, a living room and a room built to be a bedroom but was used as a drawing room.

The second floor had two bedrooms, a small office, and an attic garret.

The tower above the second floor featured an oil storage/workroom, a “watch room” and a 5,000 pound iron and glass “lantern room” which housed the heart of the house — the light. The lighthouse also had a basement for storage and a brick cistern which held collected rainwater for drinking and washing.

There was a sturdy roof of split face/sawn back cedar shingles.

Horizontal German style siding covered the main part of the building and vertical board and batten siding covered the tower. Windows had short, angled “hoods” to deflect heavy rains. They also had louvered shutters to shut and lock during the worst weather.

Two brick chimneys on the south end of the house vented two fireplaces on the first floor and two on the second. A third chimney was built on the north side for a large cook stover in the kitchen.

There were a lot of beautiful ornamental touches such as carved supporting brackets, newel posts and railing pickets with a scroll cut “tulip” design. None were just unnecessary “ginger bread” adornments like those found on the Cape May cottages. These features at Hereford were completely functional and extremely sturdy.

This building was indeed built to withstand the worst conditions. Except for the tower that had to “give” a bit with the wind, the main section of the house had brick work laid between all of the wall studs!

The builders of the Lighthouse must have been extremely proud of their work when it was completed. During restoration work in the summer of 2003, a discovery was made by the carpenters. Several sections of the original siding were removed and underneath on the wood sheathing, covered up for 129 years, were these words in pencil . . . Lyle J. Gurst – March 5, 1874, David Ames – 1874, Commence – November 8, 1873 – finished March 30th, 1874.

Although pleased with their work, the builders were undoubtedly very anxious to leave the isolated island and get back to their families.

The annual report (1874) of the Lighthouse Board noted that “Hereford officially was completed on April 16th, 1874 and a boathouse and boat were furnished for the Keeper.”

John Marche was appointed as the first keeper of Hereford Lighthouse and moved into the building on May 8th. A “notice to mariners” was released to all sea captains and the 4th Order Fresnel Lens was illuminated for the first time on May 11th, 1874. It’s reassuring beacon casts out 13 miles out to sea just as it still does today.