by Maureen Saraco

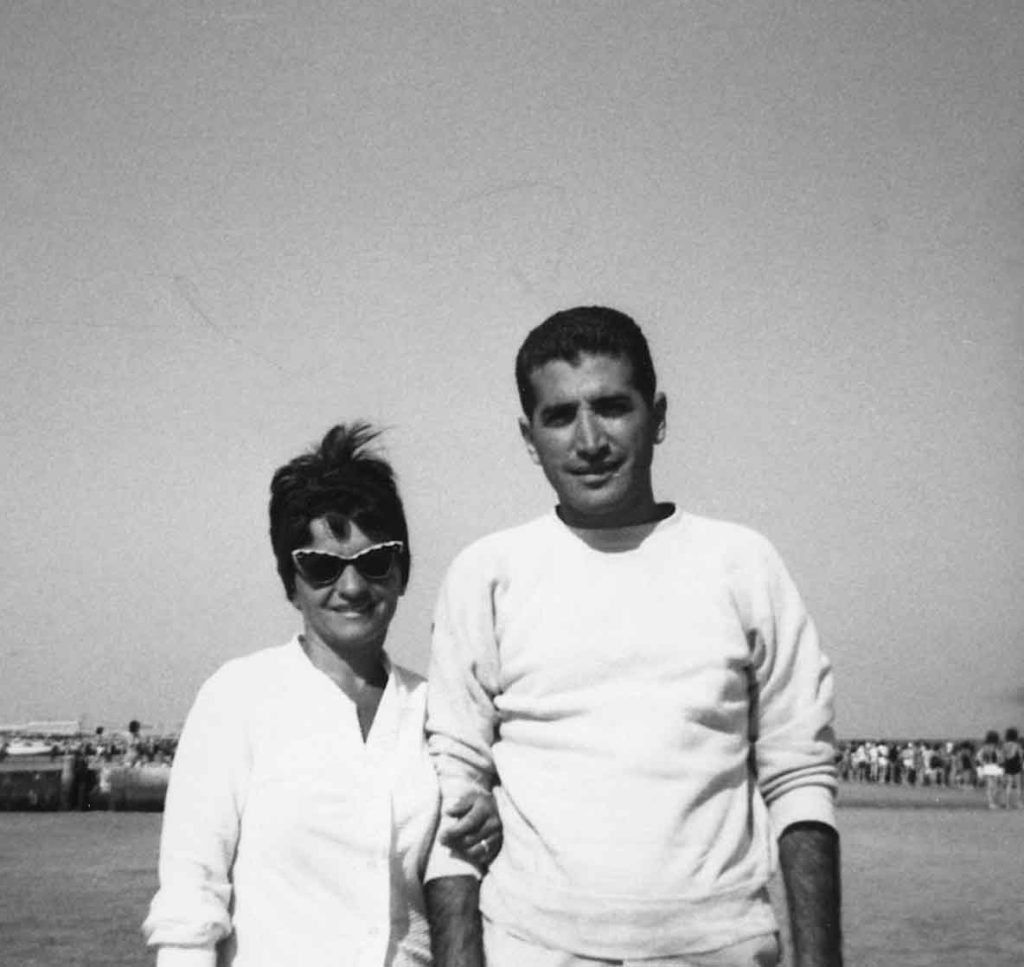

In 1956, my great-grandparents, John and Carmela Grande, left Philadelphia and bought a Wildwood house with a shaded concrete porch and green paint that would look minty if it wasn’t stained gray from windswept sand. I imagine that was the year they first discovered the writing on the attic walls. They spent their lives here, always waiting for summer. That’s when their grandson, my father, would visit. When he was little, he came only on weekends, or for a week in August when my grandfather took his paid vacation from his office job at the Naval Depot. In college, he started to stay all summer. Thirty years later, it became my turn.

I’ve never seen the writing on the attic wall, written by the boys who had what we have before we had it, and all it is, is their names and the year 1914. It’s too hard to get up there because of the toaster oven and the step stool and the rusty table fans that block the stairs. Also, the windows up there haven’t been opened in fifty years! We don’t know who they were, the four boys who knew this house before anyone in my family came to the island, who used this attic as their bedroom every summer.

These days, books with dog-eared pages and torn covers litter the small slivers of floor space between the unmade beds in one of the upstairs rooms. In the summertime, we read what we like. I sleep in this room, in sandy sheets, with my three sisters. When I’m the last one awake, reading The Great Gatsby by flashlight in the middle of the night, sometimes my thoughts drift to the four boys in the attic, and I take comfort in what can be passed down. “Can’t repeat the past?” Gatsby cries incredulously. “Why, of course you can!”

I remember my dad teaching me how to ride a wave when I was seven years old. He spun me around towards the horizon, lifted me over the ripples, and helped me wait for the right time. “Wait until the wave does that,” he said, a wave cresting with a white and foamy edge before us. I pushed up on the wet sand with the balls of my feet, lifting myself up over the wave. I came down in time to see him dive forward, just ahead of the breaking wave. He took a few long strokes, and then the wave caught him and carried him smoothly to the sand. He didn’t tell me what to do, though, when the undertow grabbed me, flipped me in circles, kept me spinning in the dark. Don’t breathe now, close your eyes. Salt. And then, finally, the water dragged me, bare-thighed, over the crushed white shells and dumped me, with hair in my eyes and water in my nose, coughing and sputtering, onto the shore. Should you experience this, you’ll discover your lungs are burning, but you suck down the air because it’s your reward for not letting yourself suck down the water. Once you know this, you understand that you can make it through anything. If you don’t give in, relief will come.

When my grandmother was my age, she chopped fudge in the oldest store on the boardwalk. Actually, in a room under the boardwalk. They used to have to carry trays of the stuff up the stairs, straining their backs so Shoobies could rot their teeth. Despite her fading memory and macular degeneration, she tells my sisters and me stories about this part of her life when we sit together on the porch on summer evenings. When everything around her starts to go dark, these stories light her up and it relieves us all.

Like my grandmother, I, too, had a sweet summer job. For three summers, I went to work at 4:50 PM and read notes from the owner, written in Catholic schoolboy script, like this one: “The price of sugar has gone up. The price of chocolate has gone up. The price of milk has gone up. The price of cream has gone up. We have two choices. We can either raise our prices, or we can SELL MORE. The theme for this summer is SELL MORE.” Every night, teenage boys twirled cherry vanilla chocolate peanut butter fudge ribbons high in the air in the store’s front window. It was a spectacle for the customers, something that made them come inside and ask for more. And when they came in (and they always did), I stopped chopping and let them scoop the soft, mushy candy up from my free sample tray with two fingers. They all said the same thing: “It smells so good.”

Do you know that smell that hits you, even when your windows are up, when you finally make it here? It finds its way in, fills you, but it doesn’t last because you’re not allowed to stop on a bridge! It’s the one that I roll down the windows for (I want more) and pull deeply through my nose. It smells like low tide and dead fish and old seaweed, like relief and home. It’s the bay and it smells so good, signaling the beginning.

Music. like smells, holds special memories. My dad’s favorite song is “Peace of Mind” by Boston. He listens to it on the two-hour drive to Wildwood, a trip he sometimes makes as many as three times a week, usually with a briefcase and laptop in the backseat. My dad is a civil attorney with his own practice. He often wakes at 5am to drive back to the city for a court appearance and usually makes it back to the shore by evening. Rarely does he stay overnight at our home in suburban Philadelphia. On days when he can stay at the shore, he still gets up at dawn to walk our dog on the beach. When he gets back, he spreads his paperwork out on our kitchen table, with the windows open and the sunshine spilling in, and works by cell phone. When he finishes, he walks the two blocks to the ocean and swims. Sometimes I don’t know why he does it, why he puts up with the early mornings and the long hours spent in the car and only seeing my mom on the weekends when she is able to join us. I don’t understand why he gave up the bigger salaries and greater prestige that came with working for big downtown law firms. Other times, it’s perfectly clear. It’s about digging his feet into the sand, staying here as much as possible, holding onto the summer before it slips away. It’s about escape and peace. I get that.

My dad had what I have before I had it. Surf Lunch was this little place up the street, where everybody got hotdogs and cokes and took them back to the beach in the afternoons. It’s where he learned that the beach is best in September. It’s when you can really find the peace that everyone comes down here looking for. He met his friends there when he was a boy. They have their inside jokes and their ‘remember-that-time’ that existed long before I did. I think why I am so tied to this place is because he is. I have friends here now too, the children of my father’s lifelong friends. When I see them with their winter coats on, it builds up on the inside, the pain that comes with the thought that it’s not yet time to go back. They’re the only ones I know who ache for this place, where warmth comes from so many other places besides the sun.

My favorite song is “Why Georgia” by John Mayer. On May afternoons, when my shoulders are still clenched and the muscles in my back are still tight, I lie on a towel with my eyes closed and let the hot sand mold itself around me. And then I listen. Sometimes over and over. I wonder sometimes about the outcome of a still verdict less life. Am I living it right?

My dad didn’t tell me what to do when it is over. I think it might be almost over. Summertime ends the way childhood does: not all at once, but as warmth slips away and cold mornings make it hard to get out of bed. You know it’s over when the pressure builds up as deep as marrow, when a few steps into the wind make your lungs burn.

My grandmother calls me once a week in the wintertime, from her apartment in South Philadelphia. She can’t see the phone anymore, but when my grandfather dials for her, and she hears my voice, I know she hasn’t forgotten me. “How are you, honeybunny?” she asks. “How’s school?” I always tell her that it’s good, even when it’s not, even when I can’t breathe for the cold and the stress, when the pressure of figuring out a life feels like that rip tide that sucked me under the water when I was seven years old. I don’t know when my next breath will come. “What will you do when you finish?” she asks. She knows it’s coming soon, even though she can’t remember exactly when. “I’m not really sure yet.” “Never do something you don’t like. Not even for a minute. You’re young. You have time. You go to Wildwood, that’s what you do. You’re like me. You’re like your father. You go home to the shore.”

When you come back to the shore, everyone asks, “How was your winter?” It’s like spring and fall don’t count. Anytime you are not here, it’s winter. The answers to this question are all variations of the same sentiment: that wherever else you were, it wasn’t here, and you’re happy winter is finally over.

I run to the water like it’s a long-lost friend, someone I lost touch with years ago and was not sure if I would ever see again. I don’t wait for my body to adjust, for the goosebumps on my arms and belly to go away. Instead, I leap, headfirst. The water rushes around me, past my ears, through my hair, and when the sand comes, it washes everything away. When I stand up, I laugh. I wipe my eyes and look out at the horizon. It feels closer, even if by just a few inches. The next wave swells up and hits me square in the stomach when it breaks. It rushes past me, and the current swirls around my ankles. I’m still standing.

I think Nick Carraway understands and said it best: “And so with the sunshine and the great bursts of leaves growing on the trees, just as things grow in fast movies, I had that familiar conviction that life was beginning over again with the summer.”